5.6 KiB

CLI or the Command Line Interface

The Command Line Interface is the most common and pervasive interface directly linking fingers typing on a keyboard (text) and the computer (commands). The CLI is a legacy mode of operating computing system which can be traced back to early telegraphic devices. In this lesson we will look at your computer's own CLI and present ways in which you can use it to write, manipulate, analyse and transform text on your own computer system.

Goals

The aim of this lesson is for readers to develop an appreciation of the advantages of using the CLI for certain types of work involving text editing on a computer. As the CLI itself is text based, our goal is to present the history of the CLI and discuss how text-based computer interfaces are still up to this day on of the most important ways to communicate with the computer systems.

The goals of the lesson are:

- Understand the historical precedents leading to the development of modern CLI.

- Acquire basic knowledge on how to operate the CLI of your own computer.

- Develop the ability to recognize where and when the CLI is a better alternative than other types of computer interfaces (mainly graphical).

- Develop a critical perspective on why the CLI matters in some situation and when it does not.

- Acquire just-enough basic CLI vocabulary to be used in future (research) work.

History

We can trace back the history of the text-based interface as mode operating computers to the telegraph and of course the typewriter. Years before computing (as we know it) was invented[REF: Turing], the telegraph was already a ubiquitous telecommunication system. Early operators of the telegraph used hand-operated devices, the Morse key, to send Morse codes down the communication cable, an interface that had many limitations due to it's rather crude operation mode. From the mid 19th century on, a few devices were invented that featured a multiple keys keyboard interface and related receiver apparatus that would print messages sent using the keyboard input device. These greatly improved the speed in which messages could be sent and received. However, messages printed using these devices were still encoded raw; a received message would usually be in punched holes format on a piece of paper tape. For this reason, trained operators capable of deciphering such codes were still key interpreters of the wired cables.

It is not until the beginning of the 20th century, with the advent of the Teletype (TTY) [REF: Crumb], that sending and receiving tele-typed text over telegraph lines was fully automated. Quite similar to the typewriter, a TTY made reading and writing encoded text seamless: the teletypewriter would encode typed alphabetic characters and the teletypeprinter would decode received encoded characters in an alphabetic format. Hence sending a message to an endpoint would be as easy as typing on a normal typewriter. This new type of telecommunication interface greatly changed the face of news and print media[REF] as it enable reporters and writers to send and receive "cables" on their own (without the need to be trained operators themselves).

But why is the history of the TTY important for our concern here? Well there's two major reasons. First, the Teletype was historically important for the development of text encoding (Lesson1). Early Teletype machines used the Baudot code encoding scheme but Teletype Model 33 (a standard TTY device in the 1960's and 1970's) used the ASCII encoding scheme. For this reason, ASCII (and modern UTF-8) has, still to this days, control characters that refer to networking operations. These characters attest the legacy of TTY devices. Second, as a result of ASCII integration in Model 33, the TTY became an central interface to mainframe computing machinery in the 1960's and 1970's. Before the advent of the TTY, the standard computing interface was the punch card format. TTY introduced direct input of computing commands from the teletypewriter and formalised the output as teleprinted on paper (ASCII also have printing control codes). For a long period of time, the main medium of computing was printed paper.1

A quick note here to emphasize the fact that computing was done on mainframes back in these days. The "mainframe" was a "colossus" computer residing somewhere in a local or remote building. As explained above, interfacing with the mainframe was done on a TTY device. This type of topology lead to the term "Terminal" to signify the user's endpoint (where the fingers and the eyes are). Much like the early TTY/telegraph coupling, a user would send computing commands on his TTY device over a network cable and receive the results back from the mainframe onto the same device. Rather than "discuss" with another fellow human over the network, you would now "discuss" with the computer.

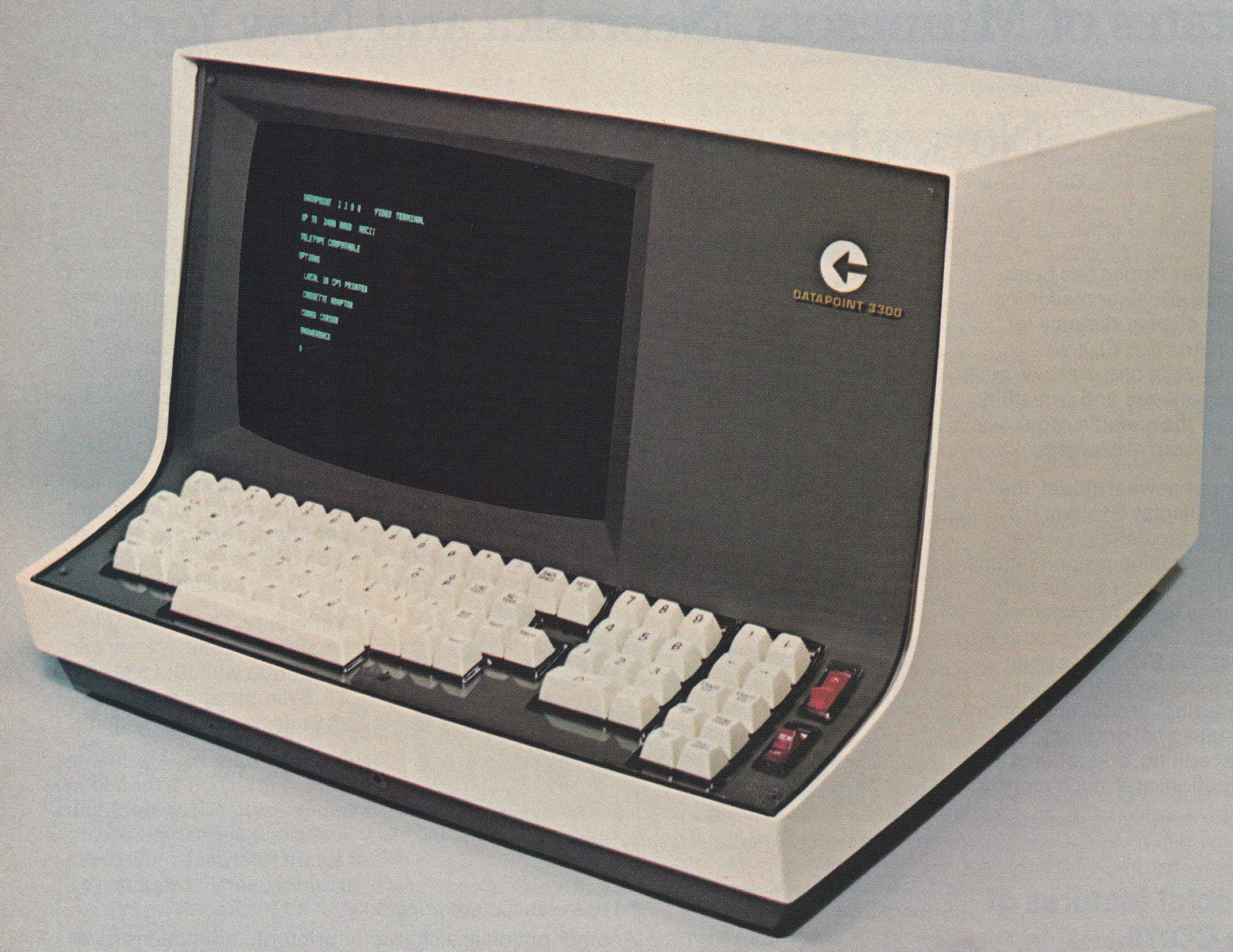

The first terminal to showcase a screen as output device was the Datapoint 3300 by

http://www.rtty.com/history/nelson.htm

TTY

Printing vs Screens

Terminals [Mainframe]

Computer Terminal Corporation -- Datapoint3300 --- first video / visual terminal Datapoint2200 --- emulation of the terminal = PC

Intel 8008 - Intel 8080

1972 UNIX

Microcomputers 1974 CP/M ( "Control Program/Monitor") DOS 1978 Apple-DOS 1979 Atari-DOS 1981 PC-DOS

How

Command Line Interface ---> Command Line Interpreter (shell)

Prompt

Commands

Results

Extra

-

Something that is easily forgotten in the era of ubiquitous computer screens. For a discussion on the topic see Nick Montfort's essay Continuous Paper: The Early Materiality and Workings of Electronic Literature. ↩︎